TheMarceloR

::Troubleshooting, Coding and Comic Books

Objected Oriented Programming With Javascript

07 Jun 2014 - Marcelo Costa

Inheritance, Polymorphism and Encapsulation

Hello fellow readers, it’s been a while since last time I blogged so here’s a quick post to review some basic OOP concepts, three of them to be more precise: Inheritance, Polymorphism and Encapsulation.

First you need to know what a class is: It is that piece of code that you can use to instantiate objects, here’s an example in Java:

public class Beer {

String name;

double alcoholUnits;

}

And a similar example in Javascript*:

var Beer = function() {

var name;

var alcohol_units;

}

*Which is not really a “class” per se as JS doesn’t have classes, but functions can be defined in specific ways so they can be instantiated as objects.

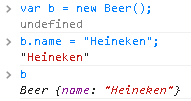

Here’s how you would test the Javascript version in your browser (Chrome’s Developer Tools or Firefox’s Firebug):

Inheritance & Polymorphism

So, moving on to Inheritance and Polymorphism, let’s use the following Friday Quiz question to illustrate these concepts:

Santa sometimes helps the elves making toys. He can make 30 toys per hour. In order to prevent getting bored, he starts each day building 50 trains and then makes 50 aeroplanes. Then he switches back to trains, and alternates until the end of the day. If he starts work at 8:00 am, at what time will he finish his 108th train?

public class SantaToys {

static Toy train = new Train();

static Toy aeroplane = new Aeroplane();

public static void main(String[] args) {

Toy toyInProduction = train;

for (double numOfToys=0;true;++numOfToys) {

if(toyInProduction.counter!=0 && toyInProduction.counter % 30 == 0){

if (toyInProduction instanceof Train){

toyInProduction = aeroplane;

toyInProduction.increment();

} else {

toyInProduction = train;

toyInProduction.increment();

}

} else {

toyInProduction.increment();

}

if(toyInProduction.counter>=108){

System.out.println("it took " + numOfToys/30 + " hours to create 108 trains!");

break;

}

}

}

}

class Toy {

public int counter = 0;

public void increment() {

this.counter++;

}

}

class Train extends Toy {

}

class Aeroplane extends Toy {

}

Let’s talk about what’s going on there, if you skip the “SantaToys” class and focus on the last 3 classes within this little program: Toy, Train and Aeroplane, you will find an example of inheritance in OOP.

Toy is in a higher level of abstraction and both Train and Aeroplane are specializations of that base class, i.e., Train and Aeroplane are toys (duh). So the cool thing about Inheritance is that it organize the entities involved in a given context and facilitates the coding process.

The subclasses inherit the attributes and methods of the parent class, in this case, both Train and Aeroplane will have their own “counter” attribute and the “increment()” method, which means, the results of the increment method will affect only that specific instance, if we increment the counter for a Train object, that means the integer value within the counter variable will be incremented for this instance only (this is another aspect of OOP languages, they have mechanisms to refer to object instances, usually with keywords like this or self). Even if you call the method from a reference variable defined through an abstract class (Toy), the correct increment method will be determined during runtime, so it’s like having a Toy that can transform itself when some action is invoked, that’s what we call Polymorphism.

Polymorphism is achieved when you use an abstract reference of an object to invoke some functionality and, as a result of the mapping of the reference variable on the stack and the actual object’s instance in the heap, different methods will be executed. Refer to the toy analogy above if this one is too boring.

So, just for the fun of it, how about implementing the same in Javascript? 😀

var Toy = function() {

this.counter = 0;

this.increment = function() {

this.counter++;

}

}

var Train = function() {}

Train.prototype = new Toy();

var Aeroplane = function() {}

Aeroplane.prototype = new Toy();

var num_toys = 0;

var train = new Train();

var aerop = new Aeroplane();

var toy_in_production = train;

for(var num_toys=0;true;++num_toys) {

if(toy_in_production.counter != 0 && toy_in_production.counter % 30 == 0) {

if(toy_in_production instanceof Train) {

toy_in_production = aerop;

toy_in_production.increment();

} else {

toy_in_production = train;

toy_in_production.increment();

}

} else {

toy_in_production.increment();

}

if(toy_in_production.counter==108) {

console.log("it took " + num_toys/30 + " hours to create 108 trains!");

break;

}

}

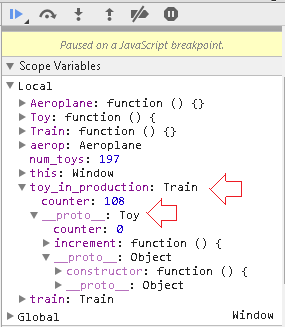

In Javascript, we don’t use the extends notation to define subclasses, instead we use prototypical inheritance to link objects in a hierarchy (there are other methods to achieve inheritance with Javascript, e.g., call() & apply() or object masquerading, but I prefer this one), in Javascript every object’s constructor has a prototype property and, in cool browsers like Firefox and Chrome, you can see a property called proto that is a reference to the prototype property of the object’s constructor, Czech this out!

| If we link this property to a bunch of key/value pairs, we can inject new properties into an object but if we assign a new object to the prototype property, then the assigned object (Toy) becomes the “parent object” of the owner of the prototype property (instance of Train | Aeroplane), that’s because, when we invoke an object’s method, the Javascript interpreter will search for that method within the object itself, if it can’t find it, it will search for it inside the prototype and it will keep doing that until it finds the method (or just returns undefined), here’s an example: |

Toy.prototype

Object {}

Toy.prototype.newFunction = function() { return "meh"; }

function () { return "meh"; }

train.newFunction()

"meh"

See what happened there? I have added a new function(method) to Toy and I have invoked the new function from the sub-object (train), Train doesn’t have the new function but its parent-object does, so the interpreter walked the Prototype Chain to find the method we were looking for.

Now that we understand inheritance with Javascript, the rest is pretty much the same, we can increment the specific instances of Toy through polymorphism and get to the result we want.

Now let’s move on to our final topic: Encapsulation.

Encapsulation

Imagine an application that manages sensitive data from a group of People (e.g., Big Company or a Bank), we can write the following classes to accomplish this objective.

public class Test {

public static void main(String args[]) {

CarbonBasedLifeform joeBloggs = new CarbonBasedLifeform("Joe Bloggs", "987-65-4320");

System.out.println(joeBloggs.name);

}

}

class CarbonBasedLifeform {

String name;

String SSN;

public CarbonBasedLifeform(String name, String SSN) {

this.name = name;

this.SSN = SSN;

}

}

In this code we create a class called “CarbonBasedLifeform” and we created an instance, Joe Bloggs, now imagine that some other programmer is adding more stuff to the program and they start messing around with some of this data, what if they change Joe’s Social Security Number? Or even his name? We don’t have anything to protect the access to the attributes of the class, so it can be easily done:

joeBloggs.SSN = "0987654321";

If people could just modify each other’s documents and alter personal data like that, what an odd, disturbing world that would be. Joe is the only one that can go through the bureaucratic loops to get a new documents, this stuff is private, that’s why it is a common practice to add modifiers to the class attributes along with special methods to control the access to their values, i.e., the Getters & Setters:

class CarbonBasedLifeform {

private String name;

private String SSN;

public CarbonBasedLifeform(String name, String SSN) {

this.name = name;

this.SSN = SSN;

}

public String getName() {

return this.name;

}

public void setName(String name) {

this.name = name;

}

public String getSSN() {

return this.SSN;

}

public void setSSN(String SSN) {

if(verifyRedTape())

this.SSN = SSN;

}

}

Now, the other classes can’t change Joe’s attributes directly, because the attributes are marked as private and the methods provide a mechanism to control how other classes interact with this data, that is known as Encapsulation or, in other words, don’t touch Joe’s privates!

In this example, the value will only be modified after Joe verifies the red tape involving his Social Security Number:

joeBloggs.setSSN("0987654321");

BTW, C# offers an interesting approach to write the same in a less verbose way.

private string name;

public string Name

{

set { this.name = value; }

get { return this.name; }

}

With Javascript, things are not so simple because, as Douglas Crockford described: “objects are collections of name-value pairs”, so we can dynamically define any property to any object any time we want, one approach that can be used to hide the value of a variable is to use Closures:

var Person = (function () {

var SSN = "";

function Person(name, SSN) {

this.name = name;

/* Preventing any changes on the SSN property */

Object.defineProperty(this, 'SSN', {

value: "",

writable : false,

enumerable : true,

configurable : false

});

this.getSSN = function() {

return SSN;

};

this.setSSN = function(ssn) {

console.log("Check red tape here");

SSN = ssn;

};

this.setSSN(SSN);

}

return Person;

})();

When the object is instantiated, it executes the IEF (Immediately-Executed Function) and returns the inner “Person” function that holds a special reference to the variable SSN in the outer function (i.e., closure), this variable can only be accessed by the public methods within the object that is returned, so it simulates the behaviour demonstrated in the Java class.

var p = new Person("Marcelo","444");h

Check red tape here

undefined

var p2 = new Person("Joe","777");

Check red tape here

undefined

p

Person {name: "Marcelo", SSN: "", getSSN: function, setSSN: function}

p2

Person {name: "Joe", SSN: "", getSSN: function, setSSN: function}

p.setSSN("111")

Check red tape here

undefined

p2.setSSN("222")

Check red tape her

undefined

p.getSSN()

"111"

p2.getSSN()

"222"

p.SSN = "999"

"999"

p.SSN

""

In summary, the encapsulation is used to protect the data within an object and also to manage the access to this data, although it is not recommended to blindly create getters & setters for all your objects without a good reason, it is a common practice in OOP and, specifically for Java, Object Relational Mapping (ORM) frameworks (e.g., Hibernate) rely on this coding convention in order to abstract the database interaction using the objects’ instances.

So that’s it for today, please share your comments below and let me know if you liked today’s post. Excelsior!