TheMarceloR

::Troubleshooting, Coding and Comic Books

Damn You Localhost! ...and Other Musings About Documentation

07 Sep 2015 - Marcelo Costa

We code stuff.

And, at some point, for some of this stuff, we create documentation.

We do this to explain how the awesome stuff we create works or to provide some guidance to layman on how to use it. Sometimes even both pieces of information are provided. People forget stuff, move to different companies, different teams, they die or convert themselves to Orthodox Latvian. For whatever reason, there’s a point where a given piece of technology has to be maintained and extended, and the documentation is one of the pillars of such endeavour.

There are many formats that can be adopted when it comes to documentation:

Official documentation: Vague, dull and filled with subliminal messages that reinforce the brand around the software’s manufacturer. Blog post / Wiki page: Way better. Sometimes hosted internally in some web-based collaboration system, Blogs and Wikis are widely used to document whatever is developed and can be extended through comments the and collaboration of all the team members. Personally, I like Blogs. The informal tone of it makes me enjoy the learning process. The code: Behold the pseudo-axiom that states “The code IS the documentation”. It is never outdated and, if done with elegance, it is clear enough to guide everyone through the understanding of whatever has been implemented. Code comments can at times smooth things up depending on how cryptic a given snippet of code is perceived. The ticket: Provides full awareness of the timeline of the story / task /defect. If you have some sort of Agile Planning or bug-tracking solution that connects to the actual source-code management system, that is even better. However, it gets polluted really fast with comments, misleading information and attachments (logs, screenshots). But of course, there are other ways to document things, some interesting practices might involve recording a presentation followed by a demo, uploading the slide deck, making the video available somewhere. How about a podcast with your fellow programmers? Or perhaps letting the newcomers dig through the code and ask them to produce the documentation as part of their ramp-up process?

The catalyst for this post was an incident that happened a long time ago, in a galaxy far far away. One of the Ops guys followed some instructions on a wiki page to recreate some collections in a SolrCloud environment, and the instructions had something similar to this:

Once you ssh into the server execute the following command: http://localhost:8983/solr/admin/collections?action=DELETE&name=theCollection The problem is that the Ops guy accidentally logged into a Production server instead of the Staging server he was looking for and, suddenly, all the indexing data from thousands of customers were gone, in the blink of an eye. I’m not exposing the exact command that was executed but, just so you known, we have proper SSL configuration to avoid any misguided interaction with our SolrCloud API, however, the usage of the client certificate is obviously granted to the Operations team.

So, here is the question: Can/Should we blame the documentation? Some might think we should integrate some additional mechanism within the existing security API to avoid such mistakes, or, even easier, we could wrap the command around a bash script that would present some scary ASCII art with skull and bones to let the user know that he is about to run that command against a particular ip address / hostname and this is a sensitive operation, anyway, regardless of the approach, this kind of goes against the “fix the process, not the problem” principle. After we restored the collection from backup, the documentation was adjusted with a placeholder:

http://

Through this exercise of sharing my personal musings involving documentation, I guess I will take a step at some compilation of best practices to create good documentation. Hopefully, the following guidelines can be adapted to different types of documentation, even if it is about architecture, features, troubleshooting steps, etc.

1 – You must have empathy

Try to put yourself in someone else’s shoes. Yeah, this one can be extremely relative and vague but, just like everything else in life, I believe it is interesting to try to leave the proper breadcrumbs and send the elevator back to help other people to reach that level of understanding you have. just imagine how amazing it would be if you could avoid all those IM windows that are constantly blinking while you try to concentrate and write some code, just reply with “RTFM” (Read The F**ing Full Manual) and send the link. Keep the following resources in mind:

- Write an overview

- Provide links to other resources

- Expand acronyms

- Collect feedback once you post it and amend if necessary

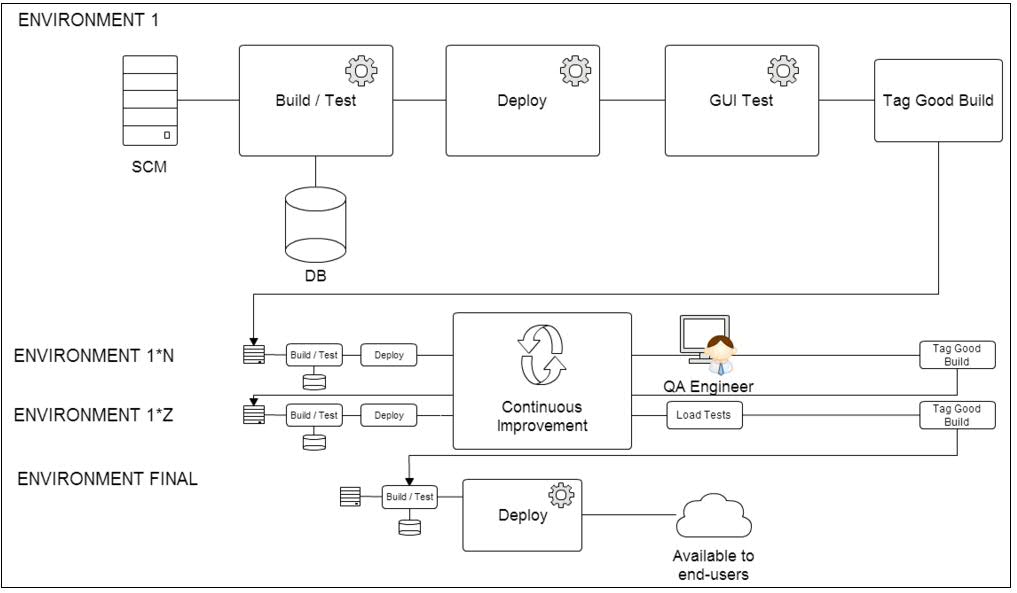

2 – Help the visual learners with some diagrams

Describe the basic architecture and, perhaps even dive into the components involved in the request flow. For automated operations, another idea is to describe a timeline of events and present the entities involved in the orchestration. Use point #1 as a guidance on which visual elements would be more appropriate for the scenario you are working on.

3 – Name it, tag it and categorize everything

The documentation you create is useless unless it can be found. So make sure you put some meaningful name and add some tags to make it easy for your internal collaboration system to index it properly. Group the pages into sections that make sense and advertise your documentation in your next technical update or knowledge sharing session.

Of course, there is no silver bullet. The documentation will become outdated, even the code can turn into a misleading amalgamation of legacy and working methods (some people don’t realize they have a version-control system so they decide to leave old stuff in the code “just in case”). However, with the proper set of references, links and comments (or other forms of general collaboration), there are alternatives to find the up-to-date information, either by going to the ticket and checking the latest updates on it or by checking the commit history of the components associated with the use case under investigation.

Now, I want to collect some feedback on this post so just comment if you feel there is something missing here.

Cheers!